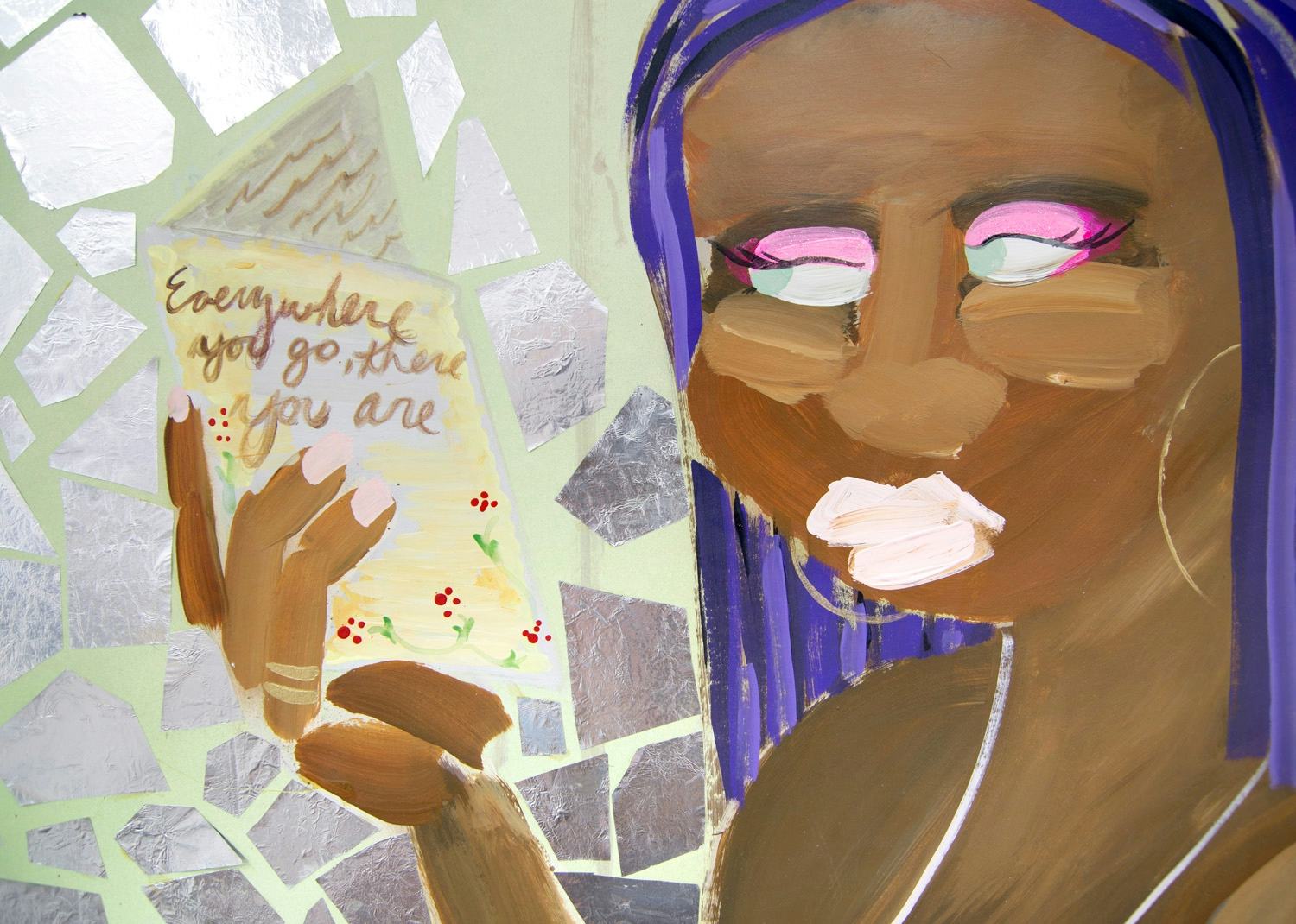

Chelsea CulpritBlessed With a Job

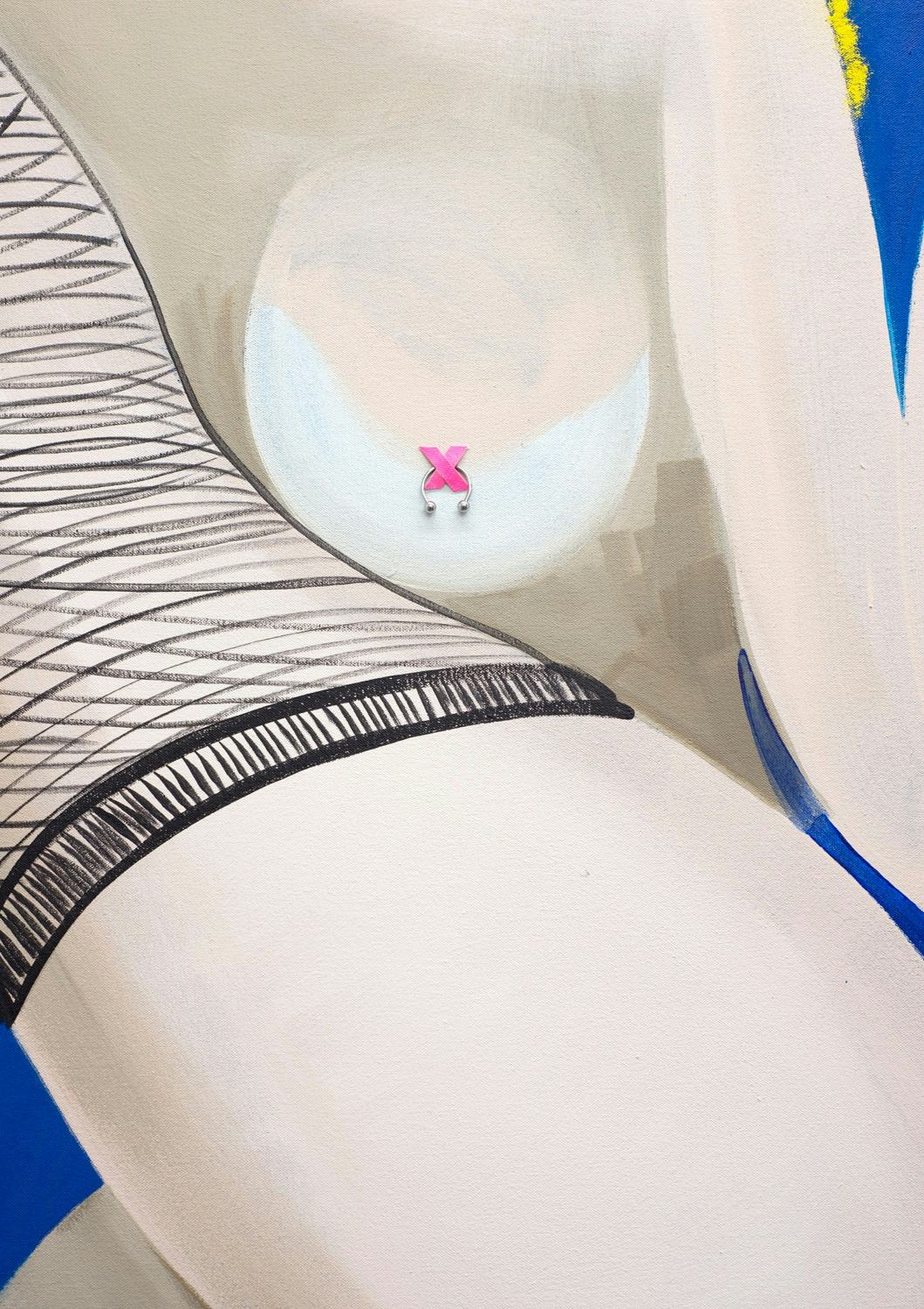

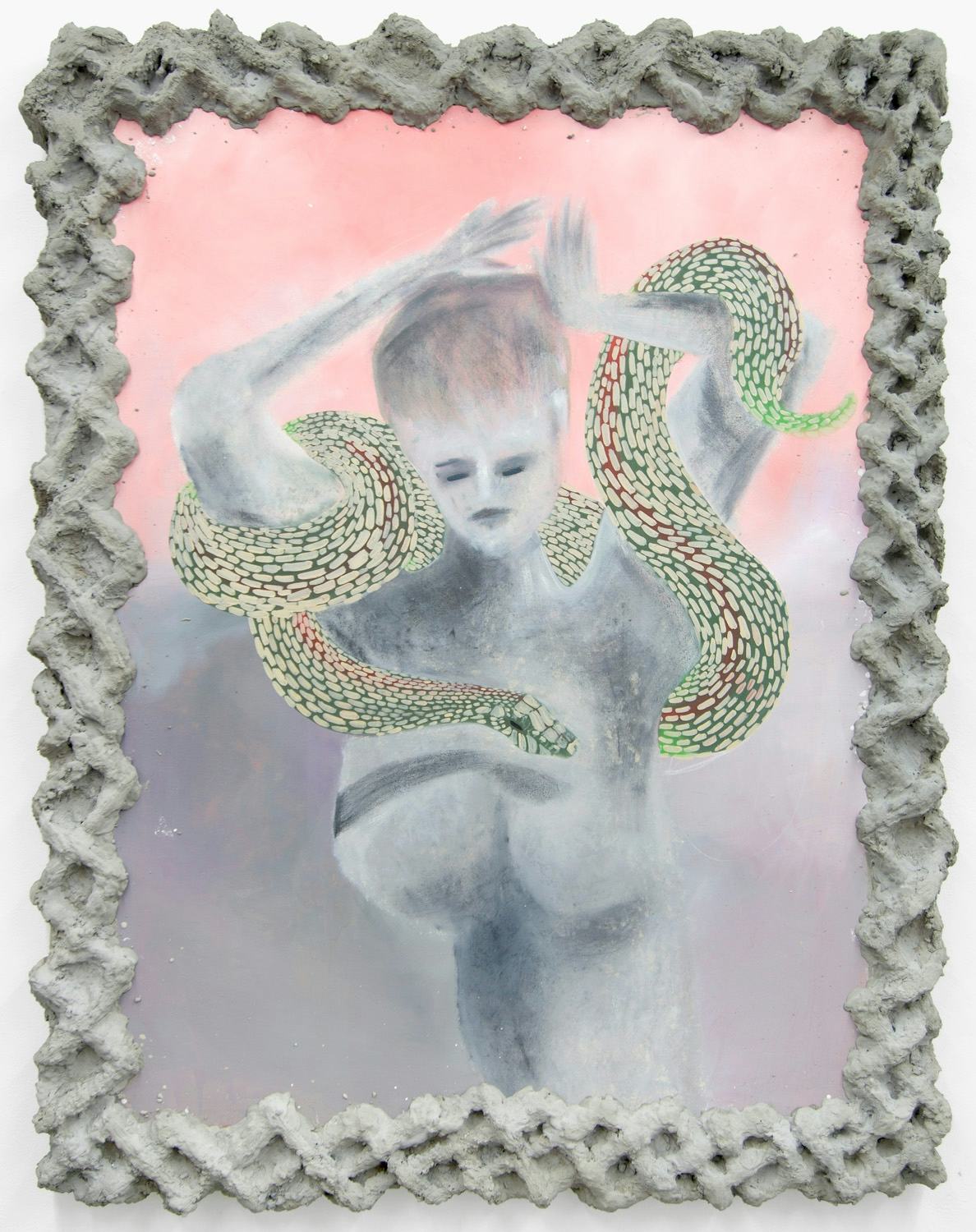

Elektra, 2016

Oil and mixed media on canvas with fabric and vinyl panels

60 x 50 inches

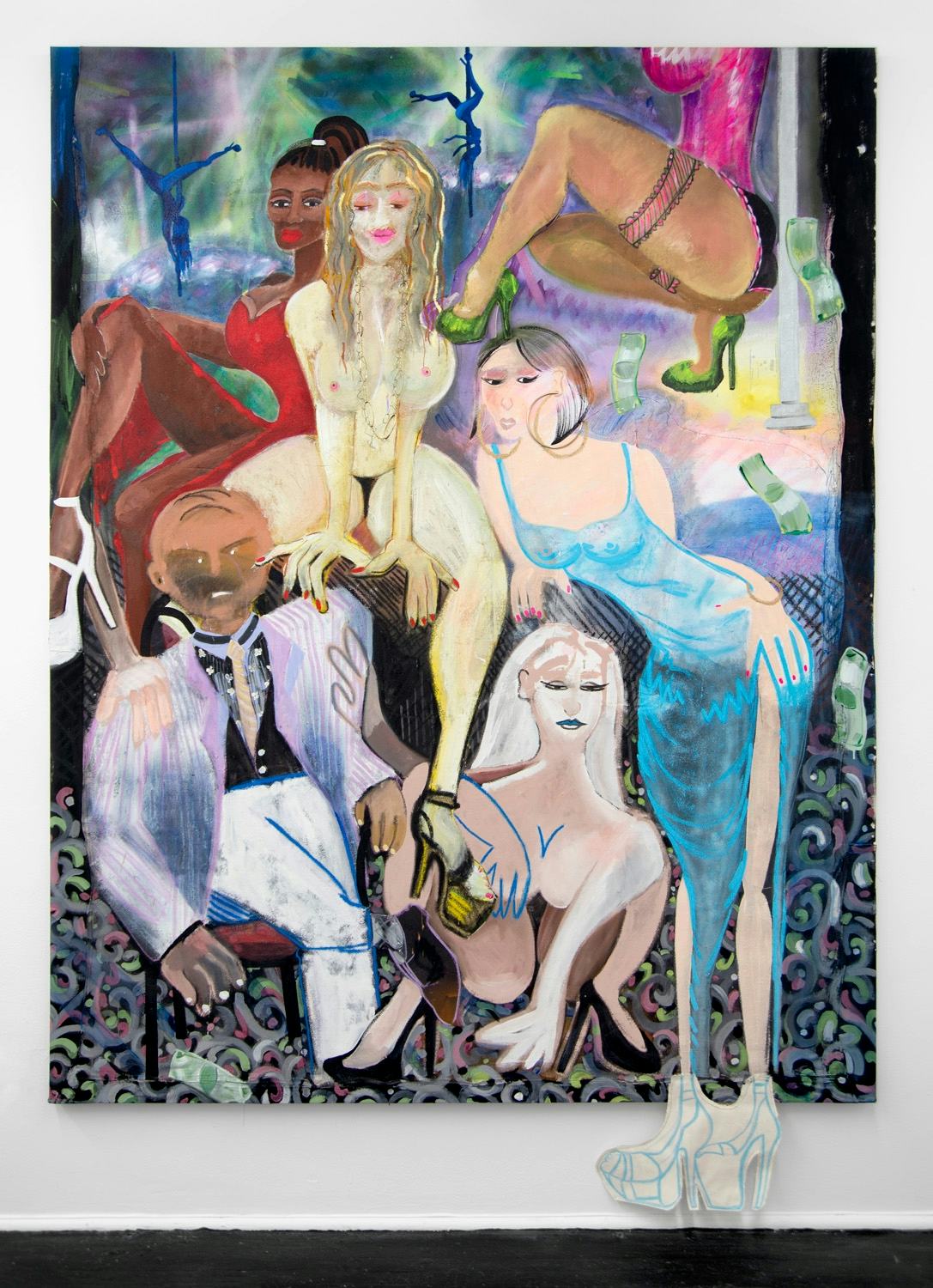

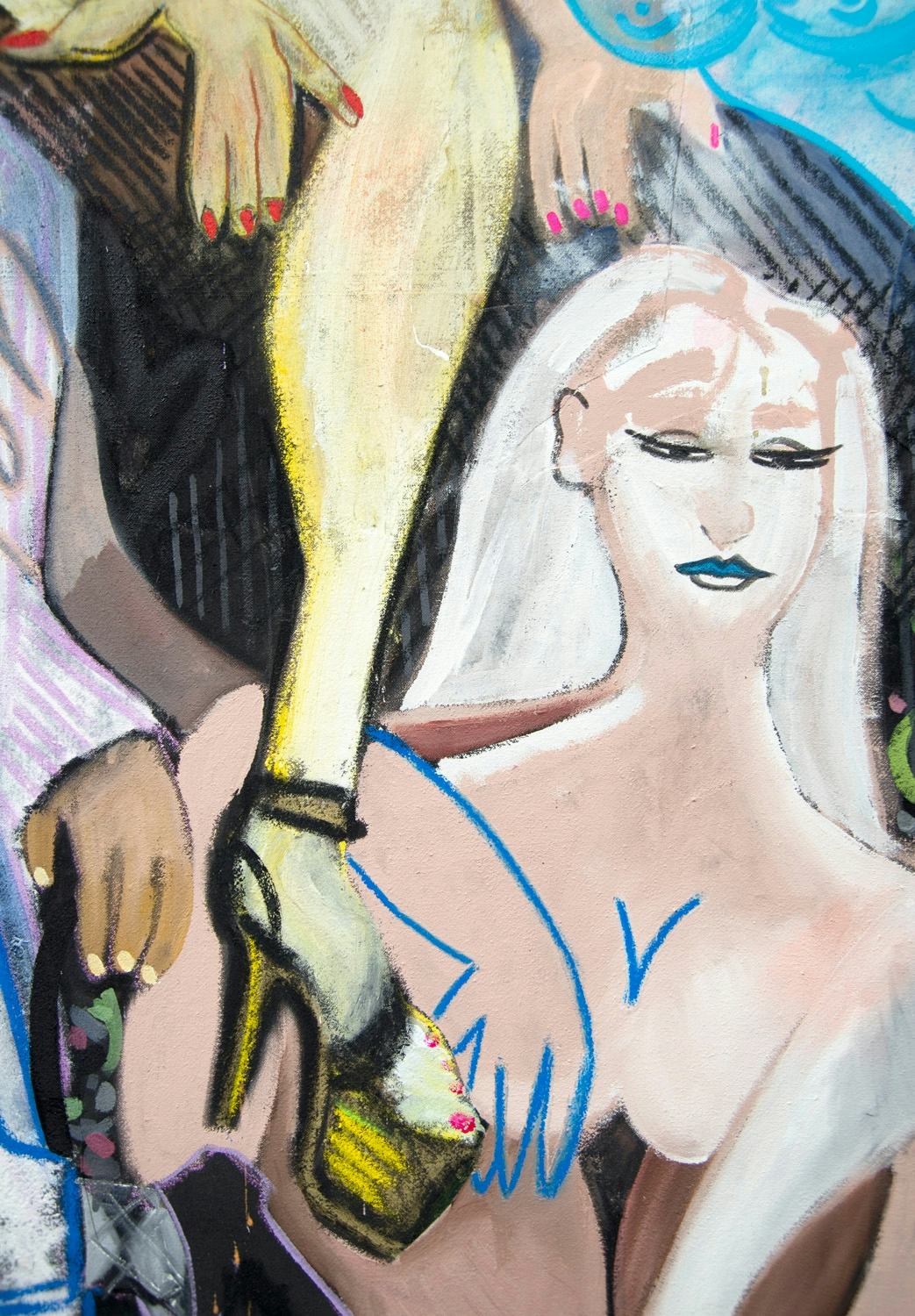

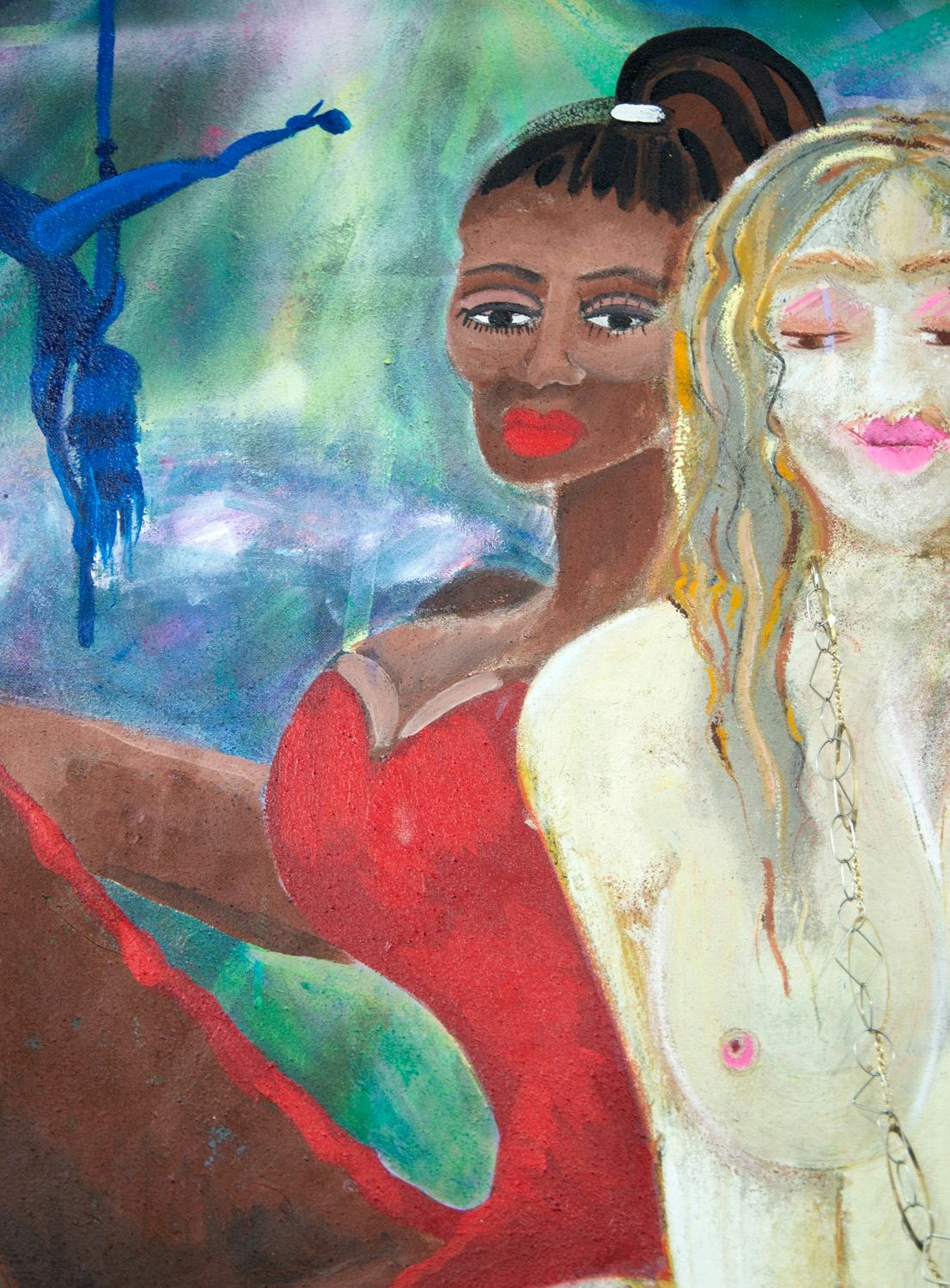

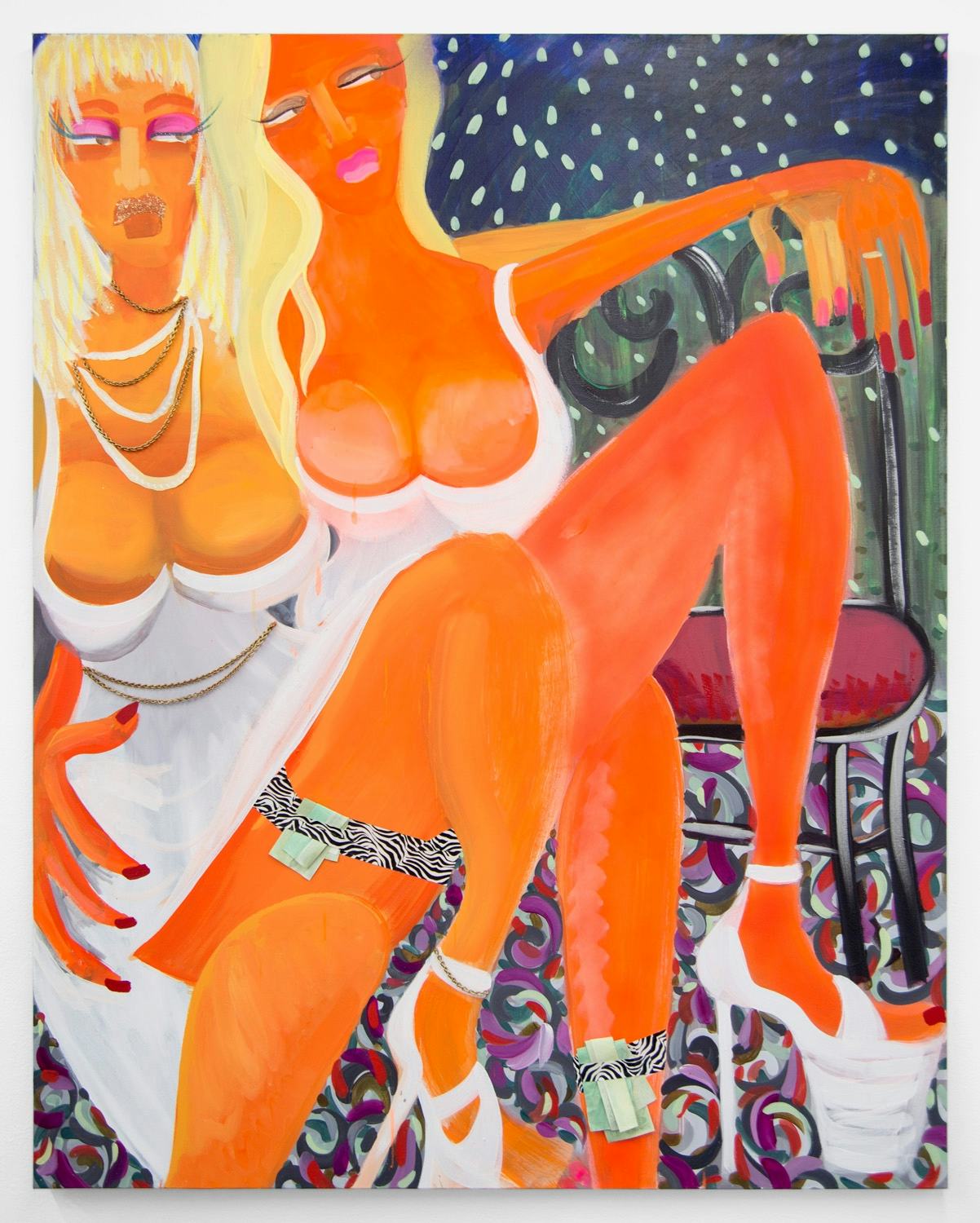

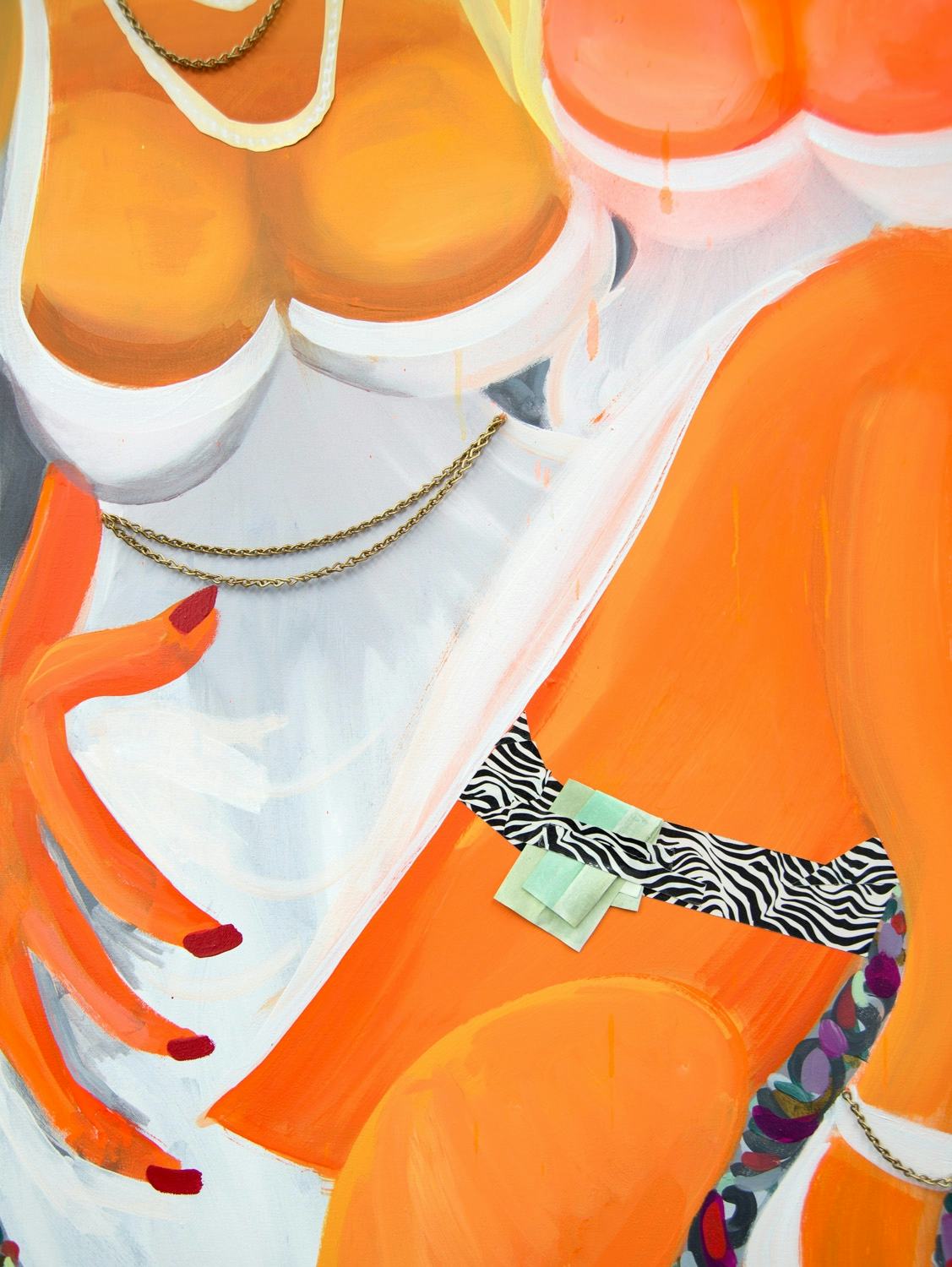

Slow Monday, 2014-2016

Oil and mixed media on canvas

106h x 75w inches (271h x 190w cm)

Blessed With a Job: Some Unsystematic Thoughts on Chelsea Culprit

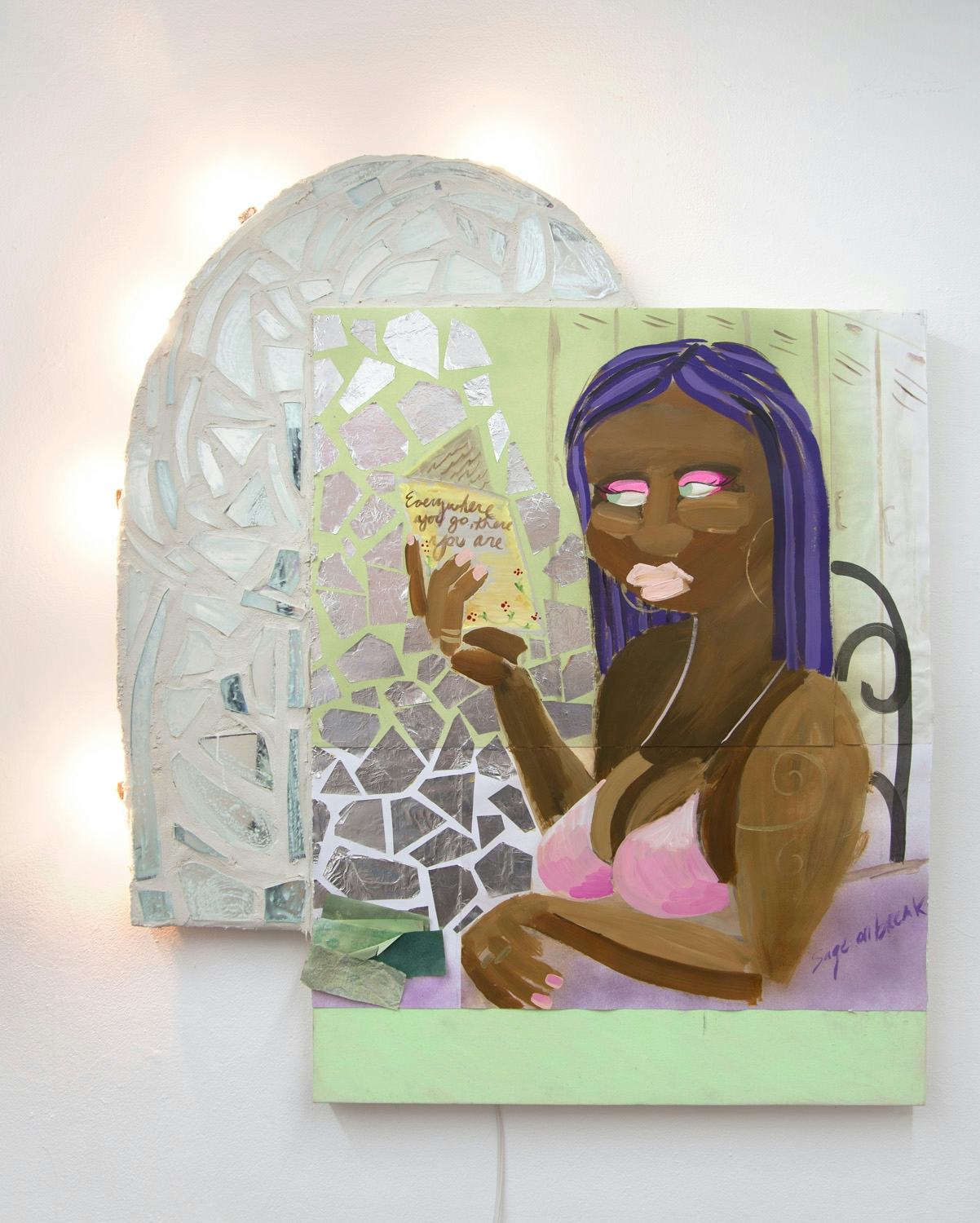

The work of Chelsea Culprit entangles representations of the body’s capacity for work, play, display, expression, the performed authenticity of identity, and the intractability of freedom and personal bondage.

A picture is an identity machine. When we look at ourselves pictured we see a finally-stable vision of personhood (an alleviation yet a delusion still). But as picture-viewers we are also given the opportunity to consider critically what we are really craving in the act of looking. In other words, pictures can compound our delusions but they can also offer us a way out from under them.

The women depicted in this show, whose job (stripping) entails the aiding and abetting of their transformation into a living image, can be pictured in a way that engages the paradox of being at times invisible and at other times on display. We can ask questions: Are these pictures more like windows or mirrors? Are these women more like themselves or more like us? Must we all be positioned as buyers or sellers in this world? And can our cosmopolitan life break out of its cycle of engulfment and isolation?

Restated in spatial terms, none of us has ever been in an empty room, for there was always our own insurmountably present body. You can’t not displace space; the body always has to be somewhere. Even the escape into a picture anticipates this fact. But it counters with the possibility of empathy, in that Renaissance picture-illusion sense, the one that kindly invites our entrance into a picture’s world. Scaling the experience up, to be in this exhibition and among its pictures, recasts these women as people less to be looked at, more to be among. Can a picture rob a look (theirs and ours) of its motive, from one of lust into a look of pure love which is motiveless?

Maybe these pictures, built as they are from divergent formal strategies of painting, are up to the task. Painting’s unique obsession with its own façade, both poignantly cultivated and grotesquely physical, creates a skin upon which we twist and pinch at our desire. Can we imagine a surface where the modification of the body is neither beautiful or revolting, but both? A surface which excoriates a falsely sentimentalized body in favor of one as weird and moving and exciting as a living being inevitably is. A painting is literally a materialist view of the world: it’s all surface, there’s no heart of gold. And what about its politics? They’re like the feeling one gets wandering an unfamiliar city, late at night: an as-yet not codified orientation which leaves us vaguely eroticized, a little scared and totally alive.

– James English Leary